Reidhead, M., Jolly, A., Barker, R., Billings, S., Davis, P., Gatz, J. (2024, May). Looking Upstream to Dismantle Health Disparities Through Clinical-Community Integration. Missouri Hospital Association. Available at www.mhanet.com/media-library/clinical-community-integration

Expert

Mat Reidhead

Actions

Type

Topic

- Health Equity

- Population Health

Tags

Executive Summary

As much as 80% of individual health and well-being is driven by nonclinical factors that are determined by the places and context in which we are born, grow, work, live and age — the social determinants of health. In this light, the health care community is increasingly confronting the paradox that a patient’s community is more consequential to their long-term health and well-being than their genetic makeup, or access to high-quality, reliable health care. Structural factors and historic inequities that perpetuate medical mistrust impose significant barriers to the provision of place-based traditional clinical care, and meeting patients where they are.

Multidisciplinary clinical-community integration is beginning to upend this paradox by bringing culturally congruent services and linkages to traditional care.

- Community Health Workers are bringing clinical and social navigation services and preventive care into communities with a deep intimacy and understanding of the idiosyncratic challenges those communities face.

- Community Paramedics are bringing primary care into patients’ homes, providing assessment and stabilization to avert costly and disruptive avoidable emergency department care.

- Peer Recovery Coaches are helping individuals with substance use disorders overcome addiction with the same tools, treatments and techniques that were successful for their own recovery.

- Doulas are bringing continuous and wholistic culturally led care to birthing people across Missouri during and after pregnancy to reverse devastating birth disparities for underserved and minoritized mothers and newborns.

This guidance document features detailed information on existing and emerging modalities of clinical-community integration in Missouri. Featuring case studies from multidisciplinary experts and practitioners from across the state, hospitals and community partners can use this guide as a resource to identify gaps and promising mitigation strategies for the unique challenges faced by the communities they serve.

Most fundamentally, clinical-community integration is intended to dismantle disparities by empowering patients and their communities with agency and voice in navigating the intersectional pathways of health and social care.

Printable Document

Stay Engaged!

To receive email notifications pertaining to MHA events and educational meetings specific to health equity, please share your contact information.

While the phrase is well-known, its conveyance of several important yet implicit messages may be less widely understood. First, and most importantly, the phrase lays out a call to action. Genetic and congenital conditions are thankfully rare and commonly unmodifiable. However, communities and built environments are highly modifiable through policies aimed at improving access to opportunities.

Second, at its core, the phrase pinpoints a history of maldistribution in access to resources and opportunities that are prerequisites of health and well-being in the U.S. By holding differences in genetic characteristics constant, while at the same time observing place-based inequities in health outcomes, the phrase alludes to the deleterious effects of upstream social determinants of health, or upstream drivers of adverse downstream health outcomes.

According to the World Health Organization, SDOH are the “nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes… the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.” This definition leads us to another set of implicit nuances to unpack, for example, what are “the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life?”

One example is the long-tailed, intergenerational effects of historic and systemically racist policies and practices, such as redlining real estate and access to capital, that have rendered opportunities for upward social mobility impossible for marginalized and minoritized communities. Home ownership is a significant driver of intergenerational wealth accumulation. As a result of prohibitions on home ownership and forced segregation through redlining, it is estimated that the average Black family would need 228 years to accumulate the same wealth as the average white family in the U.S. today. This speaks to the vicious cycles perpetuated by systemic disparities since Jim Crow — for example, primary and secondary education is mostly funded through local tax bases, including in locations where that tax base has been intentionally deflated by limiting opportunities for wealth accumulation.

This historical and ongoing disinvestment in communities segregated along synthetic racial and ethnic compositional lines underscores the need for investment in underserved communities, in addition to restoring trust between the health care system and community members by serving them in the communities where they are “born, grow, work, live and age.” One such strategy involves increasing access to culturally congruent, place-based care through clinical-community integration specialists.

Intersectionality of Health Outcomes:

Black infant mortality is more than double the rate of white infant mortality in Missouri. Pregnancy-associated mortality for Black birthing people in Missouri is triple the rate of white birthing people.

These devastating disparities for newborns and prime-aged birthing people are major contributors to life expectancy for Black Missourians being more than five years less than their white neighbors.

Clinical-community integration is centered on upending the ZIP code versus genetic code paradox by serving communities in the places where its people are “born, grow, work, live and age.” Clinical-community integrationists — Community Health Workers, Doulas, Midwifes, Community Paramedics and Peer Recovery Coaches, for example — work within communities in collaborative settings between health care providers, community members and communitybased organizations that are designed to create direct linkages between traditional settings of health care delivery (clinics, hospitals, etc.) and historically underserved communities. Strategies are designed to recognize and address multietiological upstream drivers of downstream health outcomes. The discipline is centered on whole-person care, acknowledging that health is a function of myriad factors beginning early in one’s life. Clinical community integrationists understand that health is a sociobiologic cycle of upstream policies and social constructs resulting in disparate downstream outcomes.

For an example of these causal linkages, birthing people without access to prenatal care are three to four times at risk of pregnancy-associated mortality, while their newborns are three times as likely to be low birthweight and have five-and-a-half times the risk of infant mortality. Later in life, people born with low birthweight are more susceptible to chronic health conditions including respiratory disorders, sensory impairments and developmental delays. Communities with limited access to prenatal care are more likely to be underfunded and as a result, have underperforming primary and secondary education systems.

For school-aged children and adolescents who were born with low birthweight, excelling in these educational systems that are intended to be a springboard for upward socioeconomic mobility is even more challenging. They are two to six times as likely to have poor educational outcomes compared to their normal birthweight peers, holding the quality performance of their schools constant.

Moving into adulthood, people with poor educational outcomes also are more likely to have lower socioeconomic status. Low SES results in chronic exposure to at least two common drivers of toxic stress — extreme poverty and food instability. People living in historically disinvested, low-SES communities also are more likely to have repeated exposures to toxic environmental stressors including crime, excessive policing and disproportionate representation of justice-involved individuals. In turn, chronic exposure to toxic stress induces physiological, behavioral and chemical changes in the mind and body that can result in the adoption of risk behaviors. These chemical, physiological and behavioral responses to toxic stress, in addition to adoption of risk behaviors often result in the early onset of multiple co-occurring chronic health conditions, which in turn lead to premature mortality.

Clinical-community integration is designed to disrupt this cycle by improving access to culturally congruent health care, preventive services and social services in historically underserved and minoritized communities. For example, a CHW may be able to connect the expectant person with culturally and linguistically appropriate prenatal care with transportation services for keeping appointments. A doula would be able to provide the birthing person and their family with in-home services to ensure a healthy outcome for both mother and child. Community paramedics would be able to respond to acute medical needs of the birthing person in their home, and peer recovery coaches could help with recovery from substance use disorders, if needed.

Breaking the Cycle:

Infant mortality for Black newborns is more than double the rate for white newborns in Missouri. Recent research shows that racial concordance in the physician-patient dyad reduces Black infant mortality by more than half, and the effects are more pronounced for clinically complex deliveries. At the same time, the most recent data show 11.3% of the Missouri population is Black while just 4% of its physicians are, producing the largest inequity ratio of population to physicians at 2.8x. Doulas are helping to close this gap. A recent metaanalysis found that Medicaid-funded doula services reduced rates of cesarean deliveries by 53% and postpartum depression by 58% to 65%. Pregnancy-related deaths for Black birthing people are triple the rate of their white neighbors in Missouri. Mental health conditions are the leading cause of pregnancy-associated mortality in Missouri. Strategies and policies designed to increase racial and ethnic representation in the health care workforce while supporting access to nontraditional care, such as doula and midwife services, carry large implications for improving birth equity in Missouri.

With requirements by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and The Joint Commission implemented in 2023 outlining the expectation that hospitals express their commitment to health equity, screen patients for SDOH and stratify health outcomes data by sociodemographic markers, many hospitals are beginning to identify community-based social risk factors that would benefit from a workforce cultivated through clinical-community integration. However, in the absence of formal reimbursement pathways, clinical-community integration strategies are perceived differently by traditional health care providers. Some are embracing these practices while others are legitimately apprehensive of care delivered in the community that may dampen patient volumes in traditionally reimbursed settings such as clinics and emergency departments. Under the current policy landscape, health systems investing in unreimbursed community-based services often feel the impact of the wrong pocket problem — a market failure in health economics where the health system incurs associated costs, while health plans accrue the returns on those investments. Conversely, apprehensive health systems typically face razor thin, or perennially negative operating margins that require constant vigilance against closure-inducing declines in patient volumes.

“MHD recognizes that improving poor health outcomes in our population requires a focus on health-related social needs, and reaching far enough upstream that we can actually prevent or mitigate the impact of those social needs on health. To that end, we are looking hard at enabling nontraditional providers, such as CHWs, Doulas, Community Paramedics and Home Visiting programs, to deliver care in nontraditional settings. These providers are much more likely to be able to meet participants where they are, helping them address immediate needs and working with them on setting goals for future health improvement outside the walls of the clinic or hospital.”

— Kirk Mathews, Chief Transformation Officer, MO HealthNet Division, DSS

What is a Community Health Worker?

A Community Health Worker is a trusted member of the community they serve, allowing them to act as an intermediary between the community and industries such as health care, criminal justice, education and social services. CHWs are unique members of a patient’s care team, currently missing in many parts of the regional health system. CHWs not only serve as advocates for patients but also provide a link between the patient and health- or social-service agencies. They work to improve health outcomes by increasing access to services and quality care, including behavioral health resources. CHWs also build individual and community capacity by increasing health knowledge and self-sufficiency through a range of activities such as outreach, community education, informal counseling, social support and advocacy.

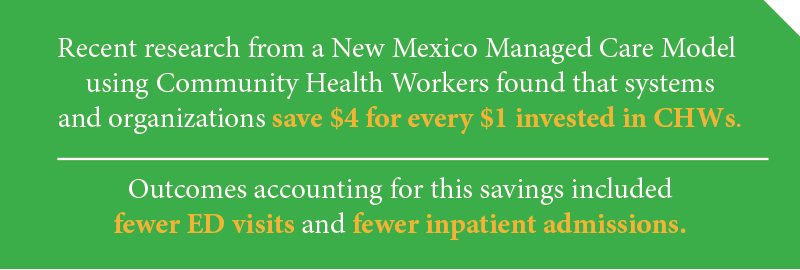

CHWs are essential to building health equity across Missouri because investing in Community Health Workers results in the following.

- Improved health outcomes for patients

- Cost savings for the state’s health systems and Medicaid program

- Increased quality of care delivery

- CHWs becoming an essential feature of value-based care

- Greater trust from patients for health providers and state agencies

- Employment opportunities for new workforce

Recognizing the importance and impact of the CHW workforce, IHN incubated the St. Louis Community Health Worker Coalition, which in 2019 established itself as an independent 501(c)4 that is led by an all CHW Board of Leaders. IHN continues to support the Coalition and is working with UMSL to evaluate CHWs utilizing a set of regional metrics and community-based participatory evaluation methods.

CHWs in Practice

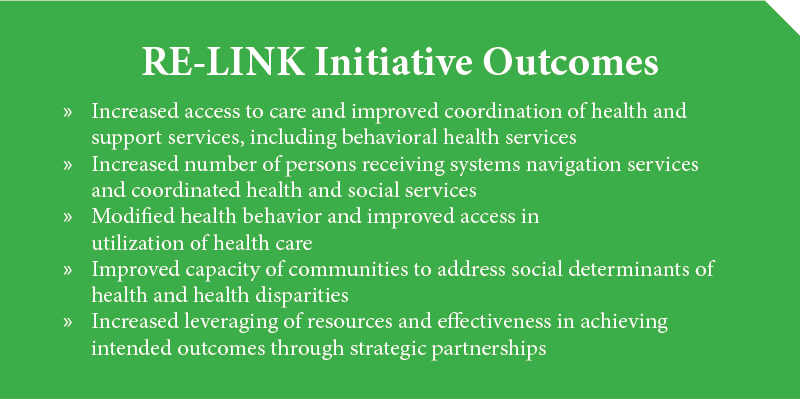

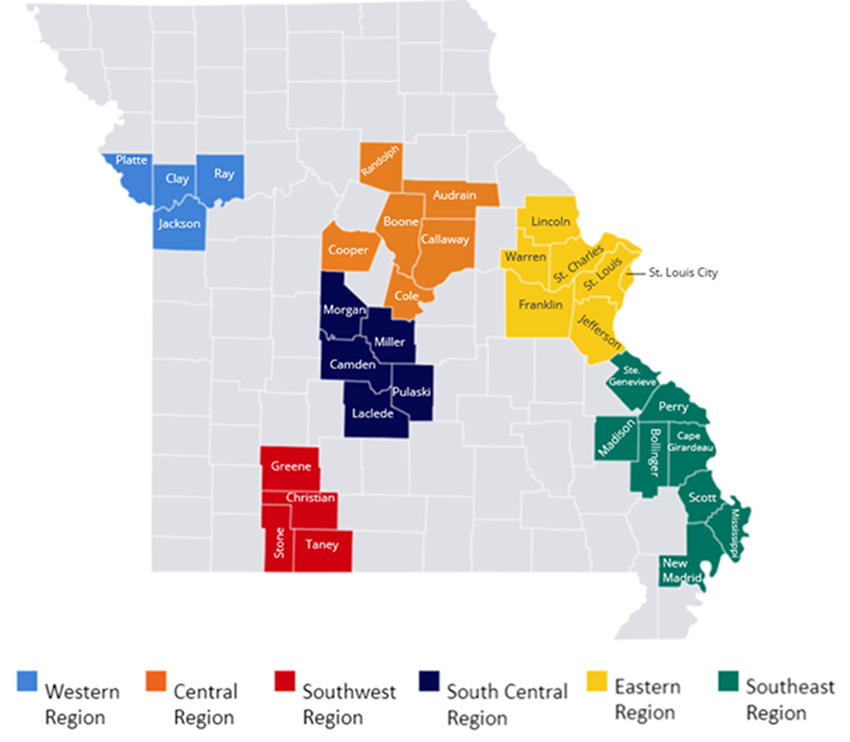

In addition to providing technical support to the CWH Coalition, IHN deploys CHWs to provide supportive reentry services for justice-involved clients through a program called Re-Entry Community Linkages (RE-LINK). RE-LINK seeks to improve health and life outcomes for placed-at-risk populations, particularly those who are racially and economically undersupported, by connecting people with community support as they transition from incarceration back home. Through a team of CHWs, the RE-LINK program links reentrants to community-based organizations that provide support and access to health care, health coverage, behavioral health and social services support. RELINK aims to develop comprehensive system coordination and navigation efforts that are culturally, linguistically and trauma-informed.

The CHW serves as an empowerment coach, mediator, advocate and systems navigator to support clients by connecting them with clinical, social and personal needs to meet goals and create self-actualization. This includes social services support, such as housing, substance use treatment, employment assistance and adult education. CHWs begin meeting with justice-involved clients pre-release to begin to establish a trusting relationship. They help them craft a plan that can be implemented upon release from incarceration, especially as it relates to housing.

IHN’s RE-LINK initiative combines one-on-one support of CHWs and connects the public health system and community support system to historically underserved individuals discharged from regional jails or prisons, or individuals involved with the justice system who are returning to the community. RE-LINK connects clients to community-based organizations that provide support and access to health care, health care coverage, behavioral health, substance use programs and social services.

By addressing social determinants of health needs, improving coordination between criminal justice institutions and the broader social service support network, connecting participants to health care, the RE-LINK program aims to reduce client recidivism. RE-LINK also partners with Saint Louis University School of Medicine’s transitions clinic, which provides holistic, trauma-informed clinical care to people impacted by the criminal justice system. Using a mobile van, the transitions clinic provides health screenings, physical and behavioral health care, and helps to bridge prescription medication needs. IHN’s Community-Based Community Referral Coordinator works with the transitions clinic to connect patients to permanent primary care homes and assist with health insurance applications as needed.

When used to their fullest capacity and training, CHWs can provide health systems with a workforce that can assist in improving quality and patient satisfaction, work with patients to connect them with social service supports to address SDOH, increase health care access and utilization, and save funds by reducing unnecessary ED and inpatient visits.

Integrating Community Health Workers

St. Louis Integrated Health Network

The St. Louis Integrated Health Network (IHN) is a health care intermediary whose mission is to build a stronger safety net for a healthier, more equitable St. Louis. One of the organization’s strategic priorities is to promote workforce stabilization and develop the health care safety net. IHN believes that Community Health Workers are part of the solution to health care workforce issues.

Opioid overdose deaths continue to rise in the U.S., and it is challenging for many people with substance use disorder (SUD) to access evidence-based recovery and treatment services. Potent fentanyl and more recently, xylazine — an animal tranquilizer — now dominate the opioid supply in many regions across the nation. More than 100,000 people died of a drug overdose in the 12-month period ending in December 2021, with more than 70,000 of these deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone. Rates of viral hepatitis, HIV and emergency department visits and hospitalizations for serious SUD-related infections also have increased. EDs are an underutilized resource in the fight against the overdose crisis, as no other setting can provide 24/7/365 access to care combined with the high-level medical wraparound services available in an ED.

Programs initiated in EDs — called “bridge programs” — offer timely evidence-based treatment, including initiation of medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), and linkages to ongoing care in the community. The Missouri Hospital Association has supported the implementation of bridge programming, Engaging Patients in Care Coordination (EPICC), in 38 counties across the state. EPICC programming provides 24/7 referral and linkage services for community members who present to a hospital for opioid, stimulant, and/or alcohol use disorder to establish immediate connections to evidence-based recovery and substance use treatment services. In each program, a team of certified peer specialists or “peers” — with lived experience of SUD — play key roles on interdisciplinary teams to help community members initiate care and access follow-up services.

The goals are to engage patients during emergency room stabilization with substance use recovery and treatment coordination and services, reduce future ED visits, provide opioid overdose education, distribute naloxone, and increase the capacity of providers offering FDA-approved medications to treat SUD. In terms of reach, EPICC bridge programming has served over 24,000 community members since December 2016. Bridge programs represent a lifesaving innovation, offering on-demand access to MOUD and other evidence-based recovery and treatment services. Evaluating the effectiveness of bridge programs in linking patients to long-term care settings remains an important research priority; however, available data show promising rates of treatment initiation and retention, a salient metric amidst an increasingly dangerous drug supply.

Learn more:

Advancing ED-Initiated Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution: Key Considerations

Advancing SBIRT for Substance Use Disorder

(Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment)

Missouri Hospital Association EPICC Program

The Transformative Value of Becoming a Trauma-Informed Health Care Institution

The Missouri Department of Mental Health describes trauma-informed care as the use of trauma knowledge to guide how treatment and services are delivered and how a trauma lens can be applied to promote organizational change.

The Missouri Model provides a framework for trauma-informed approaches to care delivery.

For more than a decade, Children’s Mercy Kansas City has been slowly, yet surely, transforming into a more trauma-informed institution. This shift has been empowered by many health care team members, leaders, departments and committees throughout the years. What might look inevitable when surveyed from the present moment is really the result of ongoing, deliberate, determined and creative collaboration across disciplines — all with the goal of improving care for our patients and supporting the resilience of our employees.

Trauma-care Efforts Grounded in Patient Needs

During her emergency medicine fellowship at Children’s Mercy, Denise Dowd, M.D., MPH, remembered seeing an article in The Kansas City Star that pictured local children killed by gun violence; she and a colleague recognized many as former patients at Children’s Mercy. They had been treated for all kinds of concerns and had been in multiple different clinics. Dr. Dowd reviewed their medical records and found that children who died from gunshot wounds were more likely to have lived in and around social-emotional, economic and physical environmental stressors. “If we’d treated trauma and chronic stress with interventions to increase physical and emotional safety,” she wondered, “would these children be alive today?” Experiences like Dr. Dowd’s led to a multidisciplinary movement to infuse trauma-informed care into every aspect of care at Children’s Mercy.

A Custom Framework for Pediatric Trauma-informed Care

Because caring for children is a specialty, Children’s Mercy has its own customized trauma-informed care (TIC) framework. Defining trauma as “any experience that overwhelms an individual, family or community’s ability to cope,” this framework is threefold:

- Awareness: An ever-growing understanding of the science of traumatic and toxic stress and its impact on long-term health and overall well-being.

- Sensitive Practices: Efforts to make each interaction with people positive, with the understanding of cultural humility, creating a safe environment, building trust, offering choice, collaboration and empowerment in care.

- Resilience at Work: Ensuring Children’s Mercy staff are supported both individually and as an organization when they experience secondary traumatic stress from a health care work environment.

A Strong Foundation Informs Trauma-informed Care Work

Children’s Mercy had trauma-informed practices in place before it had the vocabulary to label them as such. Examples include Child Life specialists who address the psychosocial concerns that accompany hospitalization and other health care experiences; its Comfort Promise, which prevents negative effects of trauma during needle procedures; CM Well, which invests in resources to support team members’ well-being; and health literacy, which is the ability to find, understand and act on health information, and is part of their commitment to equitable care. Many health care systems also have existing programs that can be counted as allies in using a TIC approach.

It Takes a Village to be Trauma-informed

Just as no one is immune to the effects of traumatic stress, it takes all members of an organization to create a cultural shift in care. “Trauma-informed care needs to infiltrate everything,” said Patty Davis, MSW, LSCSW, LCSW, IMHE(III), Trauma-informed Care program manager at Children’s Mercy. “It’s like learning a new language — and we want everyone to know the language. Our first goal is 100% awareness, no matter the employee’s role.”

Thousands of Children’s Mercy team members have completed at least one TIC learning module; the best results come when entire departments train together. This way they can make alterations to practice and policies as a team. With more employees learning TIC language and concepts, teams are discovering simple changes they can make to become more trauma-informed. From changing their approach to conversations with stressed parents to changing the wording of survey questions, Children’s Mercy employees are incorporating trauma-informed principles across the organization.

Some of that work begins right in TIC education sessions.

“A unique component of our training includes brainstorming,” Davis said. “Now that you know what you know, what can be done differently to incorporate the TIC key principles? We remind teams that TIC can be used to embellish the great work they are already doing. Our goal is to incorporate TIC universal precautions, so we have a better chance of serving all patients and families with universal safety and trust.

“Sometimes clinics realize their current policies or procedures are suitable for 80% of their population but may not be considering the effects of toxic stress of others,” Davis continued. “Without a focused effort, we may unintentionally foster health inequities. So, we started to get folks on the front lines thinking about things with that new lens. And they started to ask a lot more questions.”

Trauma-informed Transformation From Systems to Relationships

An example of a systemic trauma-informed change is the All About Me note, a multidisciplinary tool Children’s Mercy developed in 2017. The note lets teams enter TIC-specific information in a patient’s chart, so everyone providing care knows how to mitigate their (and their family’s) stress. Davis and a hospital-wide team currently are working on a project that combines All About Me with other existing psychosocial safety notes, so the information is easier to access and all in one place.

Children’s Mercy team members are integrating TIC principles into their daily work in a variety of ways. Erin Perez, LMSW, LCSW, program manager of Heart Center Patient and Family Support, shares one story of how a TIC approach helped her team serve a family more sensitively.

A mother of a child in the ICU seemed reluctant to leave the waiting room and spend time at her son’s bedside. Instead of pushing her to go, the team’s social workers and psychologists asked her about her ICU experience with curiosity and empathy, not judgment. They learned that the mother had lost her husband to the same condition affecting her son. Her husband’s death was unexpected and traumatic, and she was struggling with flashbacks.

“We had no idea,” Perez remembers. “She loved her son deeply, but she was really struggling.”

The team began going to the waiting room to update the mother instead of expecting her to come to the bedside. Knowing the team had empathy for her situation changed the dynamic. She started going to the bedside more often because she trusted the team would be extra sensitive.

“I think that’s the biggest thing about trauma-informed care — maintaining our curiosity,” Perez said.

After taking one of Davis’ TIC awareness classes, Dena Hubbard, M.D., FAAP, Neonatology Director of Quality and Safety, wanted to bring TIC training to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

“We embarked on a yearlong education for all disciplines, which was unique,” reported Dr. Hubbard. Shifting from “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?” has changed the way she and her teammates approach their jobs.

“Before the training, when I was trying to help take care of a baby, and the parent was disruptive or yelling at me or didn’t trust me, I would take that personally,” Dr. Hubbard said. “I would think, ‘Why are you being mean to me? I’m trying to do all this for your baby.’ And now I realize it’s not about me at all.”

She and colleagues outlined TIC’s effects on their department in “Trauma-informed Care and Ethics Consultation in the NICU,” which appeared in Seminars in Perinatology. The paper offers six principles of TIC care in the NICU and tells the story of how understanding a mother’s history of trauma helped the team change the way they responded to her, leading to a much more respectful, mutually trusting relationship.

“Trauma-informed care training definitely played a role in me being a better version of myself,” said Dr. Hubbard. “I am a much better clinician, physician, colleague, parent and spouse.”

Davis, Dr. Hubbard and a multidisciplinary team studied the outcomes of this comprehensive training in the NICU and found it was effective in changing belief systems through increased awareness and understanding, enhancement of self-awareness and a collective desire to mitigate bias. You can find the article published by the Journal of Perinatology here.

Sharing Knowledge, Continuing to Learn

By taking an organic, curiosity-led approach, Children’s Mercy also has established itself as a leader in the TIC space. The Trauma-informed Care Workgroup at Children’s Mercy authored TIC online training modules for Pediatric Learning Solutions, a division of the Children’s Hospital Association. As of January 2023, the two courses have been used at more than 61 pediatric hospitals and taken by tens of thousands of pediatric health care team members. Still, Davis believes the TIC learning is never over.

“As populations age, generations change, new employees join and so many other factors, we will always be on a journey to be trauma-informed,” said Davis. “It’s an ongoing cycle for any trauma-informed organization to learn and adapt to better meet the patients’ and employees’ needs.”

Providing Trauma-Informed Care

Children’s Mercy Kansas City