Expert

Shawn Billings

Actions

Type

Topic

- Behavioral Health

- Opioids

- Process Improvement

- Substance Use Disorder

Tags

|

|

|

|

The Missouri Hospital Association, Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, Missouri Department of Mental Health, and University of Missouri – St. Louis Addiction Science Team recognize the call to action needed to save lives and believe this will be accomplished, in part, with empirically supported OEND clinical protocols that are directly embedded into electronic medical records.

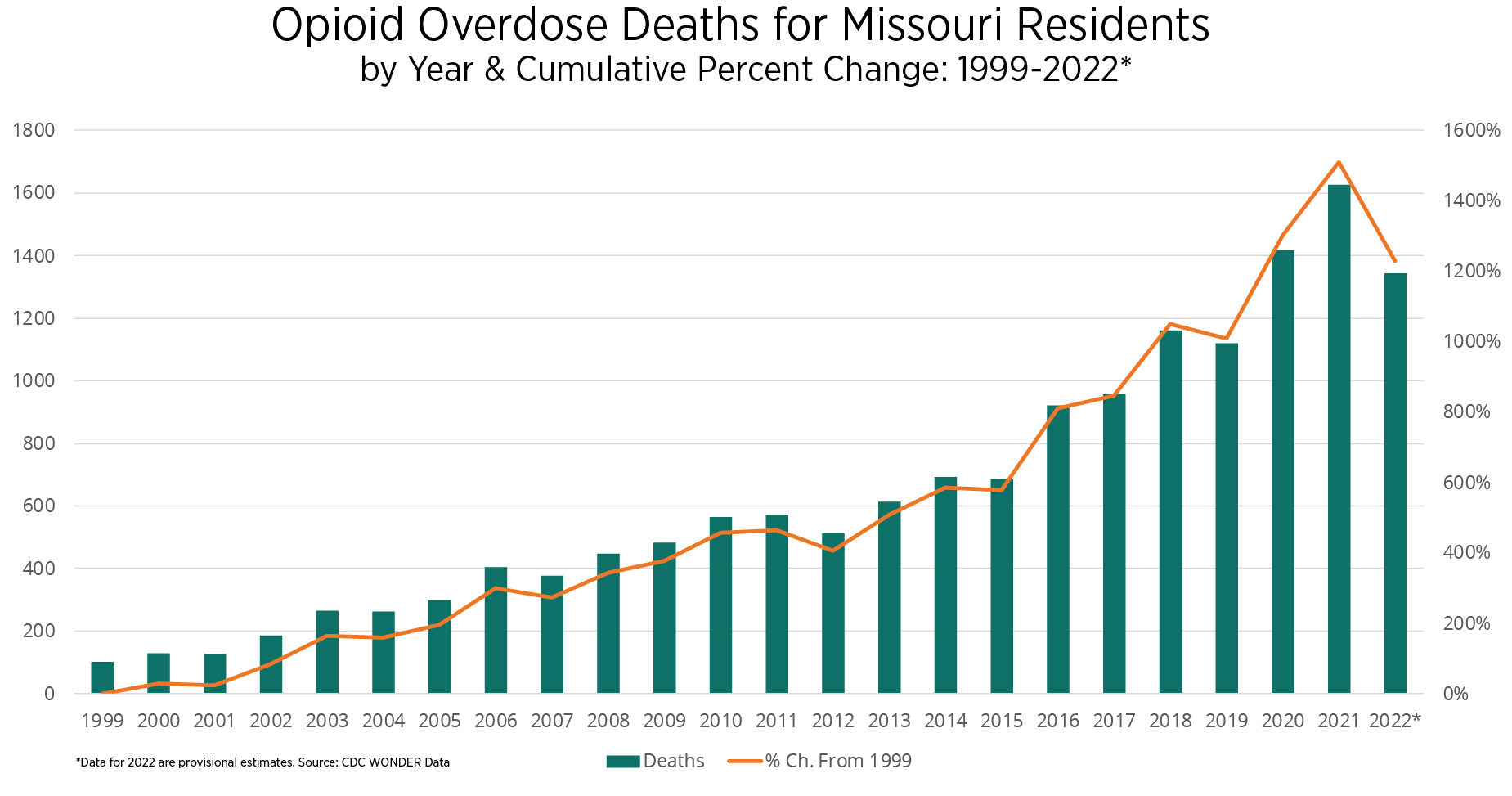

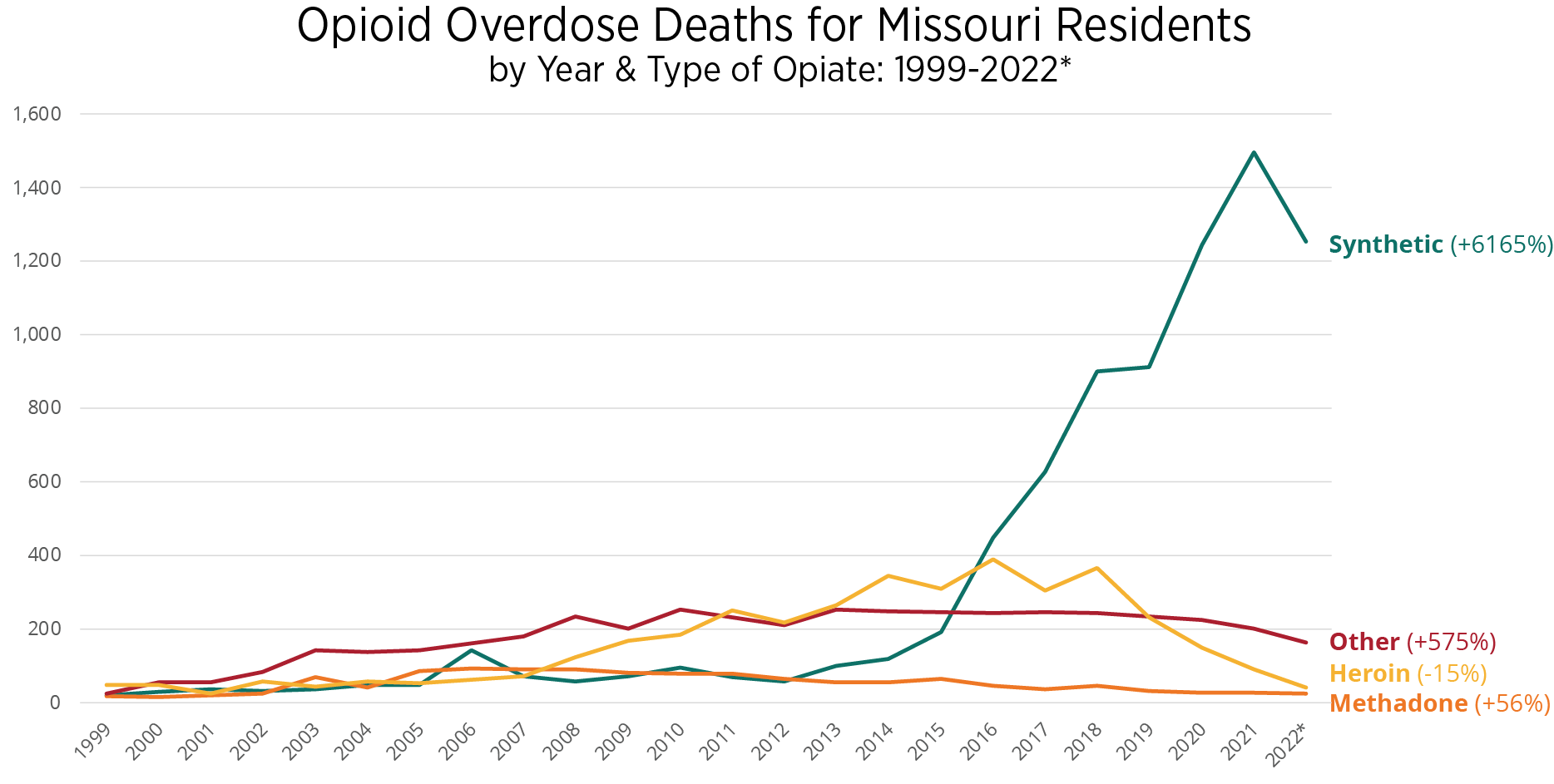

Drug overdoses are the leading injury-related cause of death in the U.S. and appear to have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overdose deaths also are increasing, and synthetic opioids, namely fentanyl, are one of the main contributors. Provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics indicate there was an estimated 107,622 drug overdose deaths in the U.S. during 2021, a 15% increase from the previous year. Overdose deaths from synthetic opioid use, primarily fentanyl, and psychostimulant use, such as methamphetamine, also increased in the 12-month period ending in April 2021.1

A printable guidance document also is available.

Naloxone, an opioid antagonist, is a medicine that instantly can reverse an opioid overdose but requires timely administration. Unfortunately, due to its cost and other limitations such as prescription status, naloxone is not always provided when it is needed most. Emergency departments treating community members who present to the hospital due to nonfatal opioid-related overdoses have an important opportunity to provide overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) before discharge. Data indicate that a risk factor for a fatal overdose includes discharge from emergency medical care following opioid intoxication or poisoning.2 Providing OEND is an effective tool to decrease the chances of a fatal overdose.

Opioid overdose-related mortality continues to present a significant public health threat to community members. Missouri experienced a 39.9% increase when comparing 36 months of pre- and post-pandemic averages.3 The following are additional key state findings.

- From 2019-2021, all age cohorts in Missouri experienced an increase in opioid overdose deaths, with the highest increase experienced by the 25-34 age cohort.

- Between 1999 and 2022, Missouri experienced a 6,165% increase in opioid overdose deaths attributed to synthetic opioids, namely fentanyl.

Considering the high prevalence of unmet substance use disorder needs among ED patients and increasing frequency of drug-related ED visits, ED practitioners are uniquely positioned to prevent opioid overdose deaths by establishing OEND programming – a simple and cost-effective way to provide a lifesaving harm reduction intervention to community members at risk for an opioid overdose. ED-initiated OEND programming should be tailored to meet local and institutional needs. Several key considerations and implementation strategies should be considered for successful integration and deployment.

FDA Approves Over-The-Counter Naloxone Nasal Spray

On March 29, 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Narcan, a 4-milligram naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray for over-the-counter, nonprescription use – the first naloxone product approved for use without a prescription. Narcan nasal spray first was approved by the FDA in 2015 as a prescription drug. The timeline for the availability and price of this OTC product is determined by the manufacturer. The FDA is working with stakeholders to help facilitate the continued availability of naloxone nasal spray products during the time needed to implement the Narcan switch from prescription to OTC status, which may take months. Other formulations and dosages of naloxone will remain available by prescription only.

Nonprescription Narcan will help supplement existing efforts, i.e., grant-funded harm reduction naloxone distribution programs and standing orders from public health officials that work to get this life-saving medication to many communities and individuals on the front lines of the opioid overdose crisis. Despite this recent approval, it will be vital that we continue to promote and advocate for increased access to naloxone for under-resourced individuals and families in our communities where the risk of overdose is highest and access to OTC naloxone may remain out of their reach due to cost.

Naloxone, an opioid antagonist, is a medicine that instantly can reverse an opioid overdose. It rapidly displaces opioids from μ-opioid receptors in the brain, reversing the respiratory depression that can cause an overdose death. Naloxone was patented in 1961 and endorsed 10 years later by the FDA. Naloxone poses no risk of abuse, does not contain analgesic properties and has no euphoric affect. The medication has been used effectively in hospital settings to treat overdoses and modulate the effects of analgesics used in anesthesia. Of note, naloxone can precipitate sudden and severe withdrawal symptoms; however, life-threatening side effects are exceedingly rare. The CDC and the surgeon general encourage that naloxone be provided to any laypeople close to opioid users, patients in substance use treatment programs, patients who receive chronic pain management, and individuals upon release from jail or prison.4,5,6,7

The efficacy of naloxone is demonstrated by decreased mortality rates, increased successful opioid reversals and increased survival rates. This success largely is dependent on the prevalence of opioid and heroin use, saturation of naloxone distribution, and level of public awareness in each community. Research clearly demonstrates a strong correlation between the number of naloxone kits distributed and a reduction in opioid overdose-related deaths.8,9,10

Figure 1.

Community Members at Risk for an Opioid Overdose

- individuals receiving emergency care for opioid intoxication or poisoning

- individuals in observation of suspected substance misuse or nonprescription opioid use

- individuals receiving an opioid prescription for pain and:

- are prescribed methadone or buprenorphine

- have a history of poorly controlled respiratory disease or infection

- have renal dysfunction, hepatic disease or cardiac illness

- have known or suspected excessive alcohol use and/or diagnosis of alcohol use disorder

- concurrently use sedatives, e.g., benzodiazepines

- are suspected to have a poorly controlled behavioral health comorbidity, e.g., depression

- individuals experiencing barriers to accessing emergency medical services, e.g., transportation

- individuals who have recently been released from prison and/or inpatient SUD treatment with a history of opioid or stimulant use

Developing and implementing OEND programming will not guarantee buy-in and utilization. Key factors affecting program integration and utilization include local, state and federal policies and laws; hospital and emergency department support; cost and payment models; and professional organizations’ guidelines.

Identifying internal hospital champions to help with program implementation and gaining support from C-suite and ED leadership early in the planning process are critical components to successful implementation. Limiting the effort required by ED practitioners can diminish provider utilization barriers and garner support. To illustrate, hospital staff can incorporate naloxone orders directly into their electronic health records system in lieu of creating a separate system or an additional process to provide naloxone. The roles and responsibilities for overdose education and the distribution of naloxone should be clearly defined. Before program launch, all relevant ED staff should be educated about the program policies and procedures — this policy should be easily accessible and housed with other ED policies.

Common provider barriers about OEND programming include negative attitudes toward community members presenting due to an overdose and/or SUD, lack of knowledge about naloxone, and uncertainty as to which patients should receive OEND. Community members receiving OEND from medical staff also could experience barriers, including stigma, fear of legal consequences for possession or use, mistrust of medical providers, and fears associated with withdrawal symptoms after naloxone administration, i.e., precipitated withdrawal.

The American College of Emergency Physicians, CDC and surgeon general all recommend that naloxone be dispensed to discharged ED patients who are at risk for opioid overdose. Notwithstanding, there remain numerous administrative, financial and logistic barriers to implementing OEND programs at individual hospitals. Previous evaluation of providing naloxone to community members who are actively misusing opioids or receiving high-dose opioids is associated with decreased overdose-related mortality.2,6,11,12 However, only one in five naloxone prescriptions from the ED actually are filled.5 Despite the increased access made possible through standing orders authorizing naloxone dispensing without a prescription, retail pharmacies do not readily dispense naloxone without a direct physician prescription.13 Key barriers identified in the Chicago-area publication include a lack of familiarity with relevant rules and regulations as applied to medication dispensation, hesitancy from hospital administrators, and an inability to secure a supply of naloxone for dispensing.

Key Hospital Recommendations:

- Engage the hospital legal department and pharmacy leaders to identify all relevant state legislation about medication dispensing and naloxone.

- Identify a C-suite champion early in the planning process to signify the importance and prioritization of OEND programming.

- If applicable, utilize 340B discount savings via the Drug Pricing Program to purchase naloxone at a discounted rate.

- Explore opportunities to fund overdose education services and naloxone kits via charitable care.

- Provide free naloxone kits, as this is an essential component of any successful ED-based take-home naloxone program.

- Identify community-based organizations that can provide additional guidance on take-home naloxone programming or donate a supply of naloxone.

- Assemble a multidisciplinary team to lead and implement the take-home naloxone program.

Effective Aug. 28, 2017, Missouri enacted the Good Samaritan Law, Section 195.205, RSMo., which is designed to save lives by encouraging people to seek emergency medical help if they experience or witness a drug or alcohol overdose or another medical emergency. Individuals who seek or obtain emergency medical assistance for themselves or for someone experiencing an overdose will not be charged or prosecuted for possession of a controlled substance under Section 195.202, RSMo. They also will not be charged for possession of an imitation controlled substance under Section 195.241, RSMo., provided the amount of substance recovered is within the amount allowed under law.

Additionally in 2016, Missouri enacted Section 195.206, RSMo., permitting the director of the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services to issue a statewide standing order for an opioid antagonist. “Opioid antagonist” is defined as “naloxone hydrochloride that blocks the effects of an opioid overdose.” Previously, only licensed pharmacists were authorized to dispense naloxone without a prescription under a physician protocol. Missouri-licensed pharmacists have two options for dispensing naloxone without a prescription.

- dispensing under protocol with a Missouri-licensed physician

- dispensing under a statewide standing order issued by DHSS

Pharmacists or the protocol physician, acting in good faith and with reasonable care, who sell or dispense an opioid antagonist are not subject to criminal or civil liability, or disciplinary action for outcomes related to the dispensation of naloxone. Under this section of law, any person, including nonmedical personnel, acting in good faith and with reasonable care, who administers an opioid antagonist to another person who they believe to be suffering an opioid-related overdose is immune from criminal prosecution, disciplinary actions from his or her professional licensing board, and civil liability due to the administration of the opioid antagonist.

Under Section 338.205, RSMo., persons and organizations that are acting under a standing order for an opioid antagonist are granted the authority to store the medication without “being subject to the licensing and permitting requirements” that regulate pharmacists and pharmacies provided they are not collecting a fee or receiving compensation for the distribution.

Missouri law also provides several provisions that specifically are related to expired medications, e.g., regulations governing long-term care facilities, and requirements of the disposal or return of expired medications. Specific regulated facilities in Missouri, including pharmacies, are prohibited from using and/or dispensing expired naloxone. Notwithstanding, no law prevents harm reduction organizations from distributing expired naloxone, and laypeople who possess expired naloxone likely can administer the medication in the event of an overdose without fear of legal repercussions.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that naloxone retains its potency long past its expiration date, even when the medication is kept in conditions that are outside the recommended temperature ranges. In one of the most comprehensive studies on the subject, expired naloxone samples were obtained from fire departments, emergency medical services and law enforcement agencies dating back to the early 1990s. Upon testing, it was discovered that the naloxone samples, stored mostly in ambulances and police cars, retained nearly all of their active ingredient even after nearly 30 years in storage.13

Guidance For First Responder Agencies

Section 190.255, RSMo., authorizes any licensed drug distributor or pharmacy to sell naloxone to a “qualified first responder agency.” A qualified first responder agency is defined by statute as “any state or local law enforcement agency, fire department or ambulance service that provides documented training to its staff related to the administration of naloxone in an apparent narcotic or opiate overdose situation.” Licensees can sell naloxone to a qualified first responder agency without a protocol. All sales/distributions should be documented in the pharmacy’s/drug distributor’s records. See the Missouri Pharmacy Practice Guide for additional information.

Individuals at risk of an opioid overdose (see Figure 1), or family and friends of someone at risk for overdose, should be offered OEND. It also should be provided upon request from patients, family members, friends or caregivers.

ED Overdose Education

Overdose education should be provided to every individual who is at risk of opioid overdose, as well as to family and friends of someone at risk for overdose. The gold standard for delivering overdose education and naloxone administration is in-person counseling.

- All ED staff should be trained in identifying patients who are at risk of overdose by implementing universal screening strategies. One such tool is the Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) protocol.

- All ED staff should be trained in harm reduction, overdose education and naloxone distribution.

- Overdose education can be provided by physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social work staff, mental health case workers, community health workers, etc.

- Educational adjuncts can be used as an alternative if in-person counseling is not available, e.g., videos and educational materials.

SBIRT has been studied since the 1960s to help identify and address the behavior of patients who are at risk for alcohol and substance use disorders.7-10 Programs that use SBIRT as a model consistently have been shown to improve the likelihood of patient follow-up and significantly reduce the risk of future substance misuse, with improved response rates as high as 70%.14,15

ED Naloxone Distribution

- Hospitals may add a naloxone dispensation order to the electronic medical record to align with the usual process for medication prescribing.

- Naloxone can be labeled with an outpatient designation.

- Naloxone can be distributed from the inpatient pharmacy or removed from ED dispensing cabinets, as applicable. Hospitals must follow 19 CSR 30-20.100 for patients being discharged from the ED or hospital.

- OEND can be given to the patient by ED staff upon discharge.

Key Considerations

Financial Impact: Hospitals are encouraged to check with their pharmacies to identify the most affordable formulary of naloxone. In general, insurance companies will not reimburse ED-dispensed naloxone as these are charged as inpatient medications – whereas insurance may cover naloxone as an outpatient medication. The following are options to cover the cost of naloxone.

- create OEND reimbursement protocols between hospitals and payers

- distribute via the outpatient hospital-based pharmacy

- absorb the cost as a community benefit or service

- apply for grants or obtain donations

- partner with community-based harm reduction organizations

Electronic Medical Record: Creating specific ICD-10 codes and prebuilt orders for the patient to receive overdose education, naloxone and recovery coach consultation (if available) will decrease utilization barriers.

Hospital Approval: After establishing an order set to provide OEND, it will need to be reviewed by the committee at your hospital that approves patient education materials and pharmaceutical procedures.

OEND Referral to Community Pharmacy, Community-Based Programming or Access Site

Referring community members to community-based resources should be utilized when direct distribution, prescribing or hospital outpatient distribution are not possible. Community members can be given naloxone without a prescription by connecting them to community-based programming, local health departments, local recovery community centers and other agencies focused on harm reduction.

Developing and deploying any program does not guarantee utilization. Identifying internal hospital champions early in the planning process is critical to any successful OEND program. Streamlining the effort required by ED practitioners, e.g., adding an OEND chart set directly into the EMR, can diminish provider utilization barriers and garner support.

The first step for establishing an OEND program is to understand the local, state and federal policies and regulations about Good Samaritan laws, standing orders, third-party prescribing, provider medication distribution and collaborative practice agreements — this will guide options for naloxone distribution. Naloxone and SBIRT are billable to insurance; however, state and local departments of health, grants and hospital funding also should be considered as sources of potential financial support. If a hospital doesn’t have the staffing infrastructure to provide in-person overdose education and naloxone training, partnering with community-based organizations should be considered. Notwithstanding, the most sustainable way to obtain OEND funding is to create program reimbursement protocols into existing billing infrastructure between hospitals and payers.

The Missouri Hospital Association, Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, Missouri Department of Mental Health, and University of Missouri – St. Louis Addiction Science Team recognize the call to action needed to save lives and believe this will be accomplished, in part, with empirically supported OEND clinical protocols that are directly embedded into electronic medical records.

Appendix 1

SAMPLE: Hospital OEND Program Checklist

- Establish an Opioid Taskforce.

- Identify providers who will develop, implement and supervise the program.

- Develop and deploy provider training.

- Establish eligibility criteria for the program.

- Develop processes, e.g., SBIRT to identify patients who meet criteria.

- Work with the IT department to establish targeted electronic health record alerts.

- Develop a standardized order set.

- Establish billing and reimbursement mechanisms to fund and sustain the OEND program.

- Identify potential sources of additional funding, e.g., grants.

- Develop processes for continuous quality assessment and improvement.

Appendix 2

SAMPLE: OEND Discharge Instructions

You were treated in the emergency department today for an opioid overdose, and your care team would like to help you avoid this risk in the future.

Opioid/substance use disorder is a chronic brain disease that can be life-threatening. We want to help you stay safe and would like to encourage you to seek recovery and treatment when you are ready.

If you are ready to begin treatment for opioid/substance use disorder:

The best way to avoid an overdose is to accept medical treatment, including a consult for medication-assisted treatment, such as buprenorphine. Inquire with your care team and ask about the FDA-approved medications used to treat substance use disorders.

If you are not yet ready to begin treatment for opioid/substance use disorder:

Even if you are not ready to begin treatment, you can take steps to reduce the harm and risk of overdose.

Identifying the substances you are putting into your body is extremely important, especially for people who inject drugs. Counterfeit pills may contain potentially lethal ingredients, such as fentanyl, which can cause overdose in very small doses.

Follow these steps to help reduce your risk of overdose death:

- Never use opioids alone.

- Try a test dose of the drug you intend to inject, especially if it is from a new source.

- Educate your family and friends on OEND, and tell them where to find your naloxone.

- Never use opioids with alcohol, benzodiazepines (e.g., Xanax, Ativan, Klonopin, Valium) or other sedating substances.

- Be careful using any drug after a period of abstinence. Abstinence can reduce an individual’s tolerance to the drug and increase the risk of overdose.

Your Take-Home Naloxone

We are providing you with naloxone that you and others can use to reverse an opioid overdose. An opioid overdose can cause brain damage or death because it impairs breathing. Naloxone saves lives by restoring breathing.

The naloxone provided to you includes a naloxone mist that is delivered through the nose. Before leaving the hospital, your care team will teach you how to use the medication. It is very important to educate your family and friends on the use of naloxone and where you store it. It is important to note that the medication expires after three years and should be stored at room temperature. Never store naloxone in a location that can get hot, such as your car.

Although naloxone can cause a rapid withdrawal from opioids that is uncomfortable and can cause agitation, administering naloxone will not place the user in any medical danger.

Appendix 3

Starting the Conversation About Naloxone

References

1 Ahmad, F. B., Cisewski, J. A., Rossen, L. M. & Sutton P. (2023). Provisional drug overdose death counts.

National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

2 Krawczyk, N., Eisenberg, M., Schneider, K. E., Richards, T. M., Lyons, B, C., Jackson, K., Ferris, L., Weiner, J. P. & Saloner, B. (2019). Predictors of overdose death among high-risk emergency department patients with substance-related encounters: A data linkage cohort study. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 75(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.07.014

3 CDC WONDER. (n.d.). Provisional Mortality Statistics. Data are from the final Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2020, and from provisional data for years 2021-2022, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Retrieved May 23, 2022, from http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10-provisional.html

4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, August 6). Life-Saving Naloxone from Pharmacies.

Retrieved August 3, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/naloxone/index.html

5 Dowell, D., Haegerich, T. M. & Chou, R. (2016). CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain – United States 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(1), 1-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1

6 Robeznieks, A. (2017, September 7). New guidance: Who can benefit from naloxone co-prescribing. American Medical Association. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/overdose-epidemic/new-guidance-who-can-benefit-naloxone-co-prescribing

7 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). When to Offer Naloxone to Patients. Retrieved August 3, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/naloxone/factsheets/pdf/Naloxone_FactSheet_Clinicians.pdf

8 Chimbar L. & Moleta, Y. (2018). Naloxone effectiveness: A systematic review. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 29(3), 167-171. https://doi.org/10.1097/jan.0000000000000230

9 Lewis, C. R., Vo, H. T. & Fishman, M. (2017). Intranasal naloxone and related strategies for opioid overdose intervention by nonmedical personnel: A review. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 8, 79-95. https://doi.org/10.2147/sar.s101700

10 Acharya, M., Chopra, D., Hayes, C. J., Teeter, B. & Martin, B. C. (2020). Cost-effectiveness of intranasal naloxone distribution to high-risk prescription opioid users. Value in Health, 23(4), 451-460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.12.002

11 Madras, B. K., Compton, W. M., Avula, D. Stegbauer, T., Stein, J. B. & Clark, H. W. (2009). Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: Comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 99(1-3), 280-295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003

12 Szalavitz, M. (2012, August 22). Preventing Overdose: Obama Administration Drug Czar Calls For Wider Access to Overdose Antidote. TIME. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://healthland.time.com/2012/08/22/preventing-overdose-obama-administration-drug-czar-calls-for-wider-access-to-overdose-antidote./

13 Pruyn, S., Frey, J., Baker, B., Brodeur, M., Graichen, C., Long, H., Zheng, H. & Dailey, M. W. (2019). Quality assessment of expired naloxone products from first responders’ supplies. Prehospital Emergency Care, 23(5), 647-653. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2018.1563257

14 Marmura, M. J., Silberstein, S. D. & Schwedt, T. J. (2015). The acute treatment of migraine in adults: The American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 55(1), 3-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12499

15 Mufson, S. & Zezima, K. (2015, October 21). Obama announces new steps to combat heroin, prescription drug abuse.

The Washington Post. Retrieved October 23, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/white-house-announces-new-steps-to-combat-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse/2015/10/21/e454f8fa-7800-11e5-a958-d889faf561dc_story.html